In 1859, an Australian landowner named Thomas Austin released \(24\) rabbits into the wild for hunting. Because Australia had few predators and ample food, the rabbit population exploded. In fewer than ten years, the rabbit population numbered in the millions. Uncontrolled population growth, as in the wild rabbits in Australia, can be modeled with exponential functions. Equations resulting from those exponential functions can be solved to analyze and make predictions about exponential growth. In this section, we will learn techniques for solving exponential functions.

The first technique involves two functions with like bases. Recall that the one-to-one property of exponential functions tells us that, for any real numbers \(b\), \(S\), and \(T\), where \(b>0\), \(b≠1\), \(b^S=b^T\) if and only if \(S=T\).

In other words, when an exponential equation has the same base on each side, the exponents must be equal. This also applies when the exponents are algebraic expressions. Therefore, we can solve many exponential equations by using the rules of exponents to rewrite each side as a power with the same base. Then, we use the fact that exponential functions are one-to-one to set the exponents equal to one another, and solve for the unknown.

For example, consider the equation \(3^=\dfrac>\). To solve for \(x\), we use the division property of exponents to rewrite the right side so that both sides have the common base, \(3\). Then we apply the one-to-one property of exponents by setting the exponents equal to one another and solving for \(x\):

THE 1-1 PROPERTY OF EXPONENTIAL FUNCTIONS

For any algebraic expressions \(S\) and \(T\), and any positive real number \(b≠1\),

How to: Solve an exponential equation of the form \(b^S=b^T\), where \(S\) and \(T\) are algebraic expressions.

Example \(\PageIndex\): Solve an Exponential Equation with a Common Base

Solution

Try It \(\PageIndex\)

Sometimes the common base for an exponential equation is not explicitly shown. In these cases, we simply rewrite the terms in the equation as powers with a common base, and solve using the one-to-one property.

For example, consider the equation \(256=4^\). We can rewrite both sides of this equation as a power of \(2\). Then we apply the rules of exponents, along with the one-to-one property, to solve for \(x\):

How to: Given an exponential equation with unlike bases, use the one-to-one property to solve it.

Example \(\PageIndex\): Solve Equations by Rewriting Them to Have a Common Base

Solution

Try It \(\PageIndex\)

Solution

Try It \(\PageIndex\)

Do all exponential equations have a solution? How can we tell if there is not a solution?

No. Recall that the range of an exponential function is always positive. In the process of solving an exponential equation, if the equation obtained is an exponential expression that is not equal to a positive number, there is no solution for that equation.

Example \(\PageIndex\): Exponential Equation with no solution

Solution

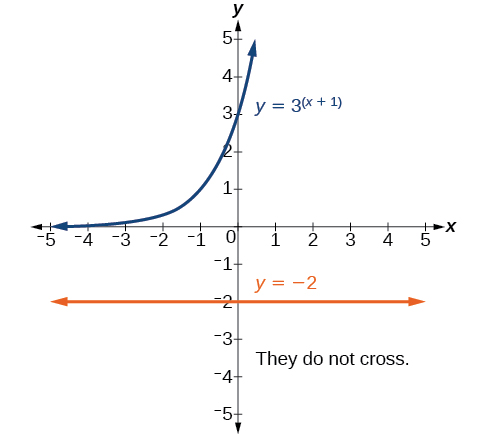

This equation has no solution. There is no real value of \(x\) that will make the equation a true statement because any power of a positive number is positive. The figure below shows that the two graphs do not cross so the left side of the equation is never equal to the right side. Thus the equation has no solution.

Try It \(\PageIndex\)

The equation has no solution.

Sometimes the terms of an exponential equation cannot be rewritten with a common base. In these cases, we solve by taking the logarithm of each side. Recall, since \(\log(a)=\log(b)\) is equivalent to \(a=b\), we may apply logarithms with the same base on both sides of an exponential equation.

How to: Solve an exponential equation in which a common base cannot be found

Example \(\PageIndex\): Solve an Equation Containing Powers of Different Bases

Solution

Try It \(\PageIndex\)

Is there any way to solve \(2^x=3^x\)?

Yes. The solution is \(x = 0\). (Take the \( \ln \) of both sides, use the power rule, and solve for \(x\)).

One common type of exponential equations are those with base \(e\). This constant occurs again and again in nature, in mathematics, in science, in engineering, and in finance. When we have an equation with a base \(e\) on either side, we can use the natural logarithm to solve it.

How to: Given an equation of the form \(y=Ae^\), solve for \(t\).

Example \(\PageIndex\): Solve an Equation of the Form \(y = Ae^\)

Solution

Analysis

Using logarithm rules, this answer can be rewritten in the form \(t=\ln\sqrt\). A calculator can be used to obtain a decimal approximation of the answer, \( t \approx 0.8047 \).

Try It \(\PageIndex\)

Does every equation of the form \(y=Ae^\) have a solution?

No. When \(k≠0\), there is a solution when \(y\) and \(A\) are either both 0, or when neither is 0 and they have the same sign. An example of an equation with this form that does not have a solution is \(2=−3e^t\), which would mean \(e^t\) is negative, which is impossible.

Example \(\PageIndex\): Solve an Equation That Can Be Simplified to the Form \(y=Ae^\)

Solution

Try It \(\PageIndex\)

Being able to solve equations of the form \(y=Ae^\) suggests a final way of solving exponential equations that can be rewritten in the form \( a = b^ \). We will redo example 5 using this alternate method. The method used in example 5 is good practice using log properties. This alternative approach uses exponent properties instead.

How to: Solve an exponential equation in which a common base cannot be found

Example \(\PageIndex\): Simplify using Exponent Rules before writing in Logarithmic form

Solution

Sometimes the methods used to solve an equation introduce an extraneous solution, which is a solution that is correct algebraically but does not satisfy the conditions of the original equation. One such situation arises in solving when the logarithm is taken on both sides of the equation. In such cases, remember that the argument of the logarithm must be positive. If the value of the argument of a logarithm is negative, there is no output.

Example \(\PageIndex\): Solve Exponential Functions that are Quadratic in Form

Solution:

Analysis

When we plan to use factoring to solve a problem, we always get zero on one side of the equation, because zero has the unique property that when a product is zero, one or both of the factors must be zero. We reject the equation \(e^x=−7\) because a positive number never equals a negative number. The solution \(\ln(−7)\) is not a real number, and in the real number system this solution is rejected as an extraneous solution.

Try It \(\PageIndex\)

Does every logarithmic equation have a solution?

No. Keep in mind that we can only apply the logarithm to a positive number. Always check for extraneous solutions.

We have already seen that every logarithmic equation \(<\log>_b(x)=y\) is equivalent to the exponential equation \(b^y=x\). We can use this fact, along with the rules of logarithms, to solve logarithmic equations where the argument is an algebraic expression.

For example, consider the equation \(<\log>_2(2)+<\log>_2(3x−5)=3\). To solve this equation, we can use rules of logarithms to rewrite the left side in compact form and then rewrite the logarithmic equation in exponential form to solve for \(x\):

Whenever solving an equation with logarithms, it is always necessary to check that the solution is in the domain of the original equation. If it is not, it must be rejected as a solution.

USE THE DEFINITION OF A LOGARITHM TO SOLVE LOGARITHMIC EQUATIONS

For any algebraic expression \(S\) and real numbers \(b\) and \(c\), where \(b>0\), \(b≠1\),

Example \(\PageIndex\): Rewrite a Logarithmic Equation in Exponential Form

Solution

Try It \(\PageIndex\)

Solution:

Try It \(\PageIndex\)

As with exponential equations, we can use the one-to-one property to solve logarithmic equations. The one-to-one property of logarithmic functions tells us that, for any real numbers \(S>0\), \(T>0\) and any positive real number \(b\), where \(b≠1\),

So, if \(x−1=8\), then we can solve for \(x\), and we get \(x=9\). To check, we can substitute \(x=9\) into the original equation: \(<\log>_2(9−1)=<\log>_2(8)=3.\) In other words, when a logarithmic equation has the same base on each side, the arguments must be equal. This also applies when the arguments are algebraic expressions. Therefore, when given an equation with logs of the same base on each side, we can use rules of logarithms to rewrite each side as a single logarithm. Then we use the fact that logarithmic functions are one-to-one to set the arguments equal to one another and solve for the unknown.

For example, consider the equation \(\log(3x−2)−\log(2)=\log(x+4)\). To solve this equation, we can use the rules of logarithms to rewrite the left side as a single logarithm, and then apply the one-to-one property to solve for \(x\):

To check the result, substitute \(x=10\) into \(\log(3x−2)−\log(2)=\log(x+4)\).

USE THE ONE-TO-ONE PROPERTY OF LOGARITHMS TO SOLVE LOGARITHMIC EQUATIONS

For any algebraic expressions \(S\) and \(T\) and any positive real number \(b\), where \(b≠1\),

Note, when solving an equation involving logarithms, always check to see if the answer is correct or if it is an extraneous solution.

How to: Given an equation containing logarithms, solve it using the one-to-one property

Example \(\PageIndex\): Use the One-to-One Property of Logarithms to Solve an Equation

Solution

Analysis

There are two solutions: \(3\) or \(−1\). The solution \(−1\) is negative, but it checks when substituted into the original equation because the argument of the logarithm functions is still positive.

Try It \(\PageIndex\)

| One-to-one property for exponential functions | For any algebraic expressions \(S\) and \(T\) and any positive real number \(b\), where \(b^S=b^T\) if and only if \(S=T\). |

| Definition of a logarithm | For any algebraic expression S and positive real numbers \(b\) and \(c\), where \(b≠1\), \(<\log>_b(S)=c\) if and only if \(b^c=S\). |

| One-to-one property for logarithmic functions | For any algebraic expressions \(S\) and \(T\) and any positive real number \(b\), where \(b≠1\), \(<\log>_bS=<\log>_bT\) if and only if \(S=T\). |

4.6: Exponential and Logarithmic Equations is shared under a CC BY license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts.